Published: Jul 17, 2024

“When you type a URL in your browser, what will happen?” If you are a web developer, you might have answered this sort of interview question once or twice. It would be a popular question to test the knowledge how the Internet works. As it is famous, you will find many answers here and there online.

A common answer includes steps below:

- DNS Resolution

- TCP Three-Way Handshake

- HTTPS Upgrade (SSL/TLS Handshake)

- HTTP Request/Response

- Browser Rendering

This blog post focuses on the first three steps: DNS, TCP, and TLS, to think how the technology conserves the network resources.

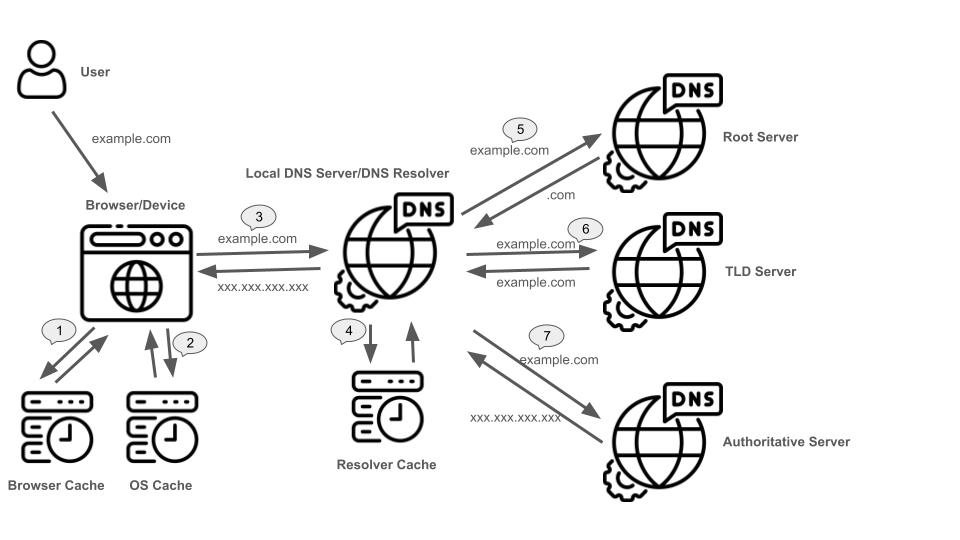

DNS Resolution

To get website contents, devices send a TCP packet. The essential components of TCP packet are a destination IP address and destination port. However it is not convenient to type 142.250.207.14, 17.253.144.10, or 54.239.28.85 in the URL box to go to Google, Apple or Amazon websites. Sure, people type google.com, apple.com or amazon.com instead of IP addresses.

The first step is to find an IP address based on a given URL string. This is done by Domain Name Service (or DNS). DNS provides a domain name to IP address mapping service and is basically a huge distributed database. As you may know, DNS servers form a hierarchical structure. On the top layer, 13 root servers are there:

- a: Verisign, Los Angels CA

- b: USC-ISI, Marina del Rey, CA

- c: Cogent, Herndon, VA

- d: U Maryland, College Park, MD

- e: NASA, Mt. View, CA

- f: Internet Software C., Palo Alto, CA

- g: US DoD, Columbus, OH

- h: ARL, Aberdeen, MD

- i: Netnod, Stockholm

- j: Verisign, Dulles, VA

- k: RIPE, London

- l: ICANN, Los Angels, CA

- m: WIDE, Tokyo

The next is a layer of Top-level domain (TLD) servers. These servers handle top-level domains such as .com, .org, .net, .edu and .gov and all of the country top-level domains such as .uk, .fr, .ca, and .jp. The third layer is Authoritative DNS servers. Many organizations run authoritative DNS servers. Among them, Cloudflare, Google and some more provides publicly accessible DNS servers.

To get the IP address from URL string, browsers/devices make queries to a local DNS server. It might be an Internet Service Provider (or ISP) DNS server and often called DNS resolver. The local DNS server asks to the root DNS server and get a referral – what TLD DNS server likely knows the domain. Then, the local DNS server asks to the specified TLD DNS server. Again, the local DNS server get the referral from the TLD DNS server. Lastly, the local DNS server goes to the specified authoritative DNS server to get the IP address.

It is a long way to finally get the IP address, however, domain name and IP address mappings are cached in certain points. A browser and OS have a cache. The local DNS server has a cache as well. If the mapping is in the cache, it is a much shorter way.

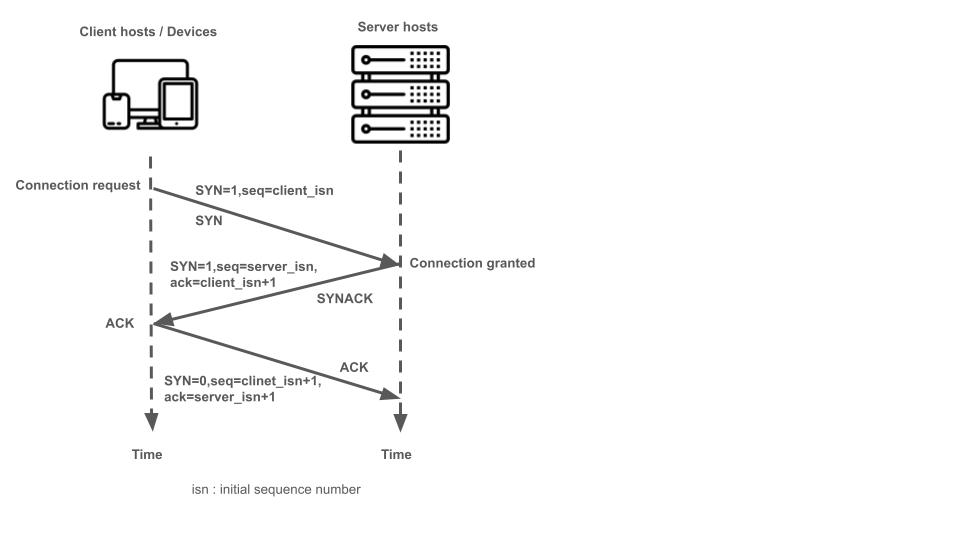

TCP Three-Way Handshake

The second step is the TCP three-way handshake. TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) is frequently compared to UDP (User Datagram Protocol). While TCP is described as connection-oriented, UDP is connectionless. TCP establishes the connection before data transfer begins. This phase is called the three-way handshake.

As the name expresses, the three-way handshake consists of 3 phases.

- Phase 1: A client sends a SYN segment, which contains SYN bit 1 and randomly chosen client initial sequence number.

- Phase 2: A server receives the SYN segment and grants it. The server sends back a SYNACK segment, which contains SYN bit 1, client initial sequence number + 1, and randomly chosen server initial sequence number.

- Phase 3: The client receives SYNACK segment and acknowledges it. The client sends back the acknowledgement, which contains SYN bit 0, client initial sequence number + 1 and server initial sequence number + 1.

After above three phases are completed, data can be sent over TCP.

HTTPS Upgrade (SSL/TLS Handshake)

The third step is TLS handshake. This handshake is much more complicated compared to TCP handshake. TLS handshake goes like this:

- ClientHello: The client initiates the handshake by sending a message containing its supported protocols, cipher suites, and random session ID.

- ServerHello: The server responds with its chosen protocol, cipher suite, and session ID.

- Certificate: The server sends its digital certificate, which contains its public key and identity information.

- Key Exchange: The client and server use asymmetric encryption to exchange cryptographic keys, ensuring secure communication.

- Change Cipher Spec: Both parties send a “change cipher spec” message to indicate they are switching to the new symmetric encryption key.

- Finished: The client and server exchange “finished” messages to verify the integrity of the handshake and ensure both parties agree on the session parameters.

Finally, web contents are ready to be downloaded to the browsers or devices.

Numbers of three steps

At this point, we learn gory details of DNS lookup, TCP and TLS handshakes. Well, let’s look at numbers related to the 3 steps above.

Number of DNS lookups

It is said that DNS traffic is extremely busy. This Hacker News post says “1.1.1.1 is now handling more than 1.3T requests per day.” The 1.1.1.1 is a Cloudflare DNS server. Only one authoritative DNS server has to deal with 1.3T requests per day! The post is 11 months ago from middle of July 2024, so data was taken around June 2023. Here is another a bit old data. A Reddit post from 2018 says, only one Pi-Hole DNS server processed around 18,000 DNS queries per day. If we think of the number of public authoritative DNS servers, global DNS lookups may go up to 10 trillion or more per day these days.

To conclude, DNS traffic is really extremely busy.

Time needed for DNS lookup, TCP/TLS handshakes

The number is from an AI assisted answer popped up by online search. So, the numbers are just an estimation.

- DNS lookup: 10-100 milliseconds

varies depending on the complexity of the domain name, DNS server performance, and network latency. - TCP handshake: 10-30 milliseconds

- TLS handshake: 200-1000 milliseconds

varies depending on the TLS version, the complexity of the certificate, and network latency.

As the unit is milliseconds, overall performance looks not so bad. However, when the sequence repeats many times, combined performance might not be negligible.

Here Comes the Keep-Alive

If you are a web developer, you are sure to know that HTTP protocol is stateless. The connection is closed once a request/response sequence is completed. When someone type the URL on the browser, a DNS look up runs followed by a TCP handshake and TLS handshake. Finally, web contents are shown up on the browser. At this point, the connection is closed. When the same person clicks a button in the web page just shown up, again gory stuff explained above repeats. The DNS lookup runs followed by the TCP handshake and TLS handshake. The same person might click another button in the same web page. The previous connection is already closed. So, DNS lookup, TCP handshake, and TLS handshake are performed, then finally, the web contents show up.

We are like: Oh, it’s a prime day. Let’s go to Amazon and click, click, click ……. Wow, what if every click triggers DNS lookup, TCP handshake, and TLS handshake? How many people on earth do click, click, click ……? The Internet world must be really extremely busy.

But, smart people are out there. They have invented a way to avoid repeating three steps. Yes, it is the keep-alive. The keep-alive is a mechanism to let the connection open. The consecutive HTTP request/response sequences can skip DNS lookup, TCP handshake and TLS handshake. Using the keep-alive improves overall web performance as well as conserves network resources. Apparently, the number of DNS look ups is cut down.

During the era of HTTP/1.0, a client or server should explicitly specify the keep-alive in the HTTP header like below:

Connection: Keep-Alive

Keep-Alive: timeout=5, max=1000

The timeout is the time in seconds that the host will allow an idle connection to remain open. The max is the maximum number of requests that can be sent on this connection.

Now, HTTP/1.1 is out. The keep-alive becomes a default behavior. Below is an excerpt from RFC2616 section 8.1.2

A significant difference between HTTP/1.1 and earlier versions of HTTP is that persistent connections are the default behavior of any HTTP connection. That is, unless otherwise indicated, the client SHOULD assume that the server will maintain a persistent connection, even after error responses from the server.

Test Keep-Alive

Well, we know Rails 7 supports HTTP/1.1, so does the keep-alive. The keep-alive should be available and working. But, is there any way to test the keep-alive is working? It is very simple. Use curl command and request twice.

Let’s try some. The first test is to make sure the keep-alive is working.

$ curl -Iv http://localhost:3000 -o /dev/null http://localhost:3000

* Host localhost:3000 was resolved.

* IPv6: ::1

* IPv4: 127.0.0.1

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 0* Trying [::1]:3000...

* Connected to localhost (::1) port 3000

> HEAD / HTTP/1.1

> Host: localhost:3000

> User-Agent: curl/8.6.0

> Accept: */*

>

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

< x-xss-protection: 0

< x-content-type-options: nosniff

#...(snip snip snip)...

< Content-Length: 0

<

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 0

* Connection #0 to host localhost left intact

* Found bundle for host: 0x600002e64480 [serially]

* Can not multiplex, even if we wanted to

* Re-using existing connection with host localhost

> HEAD / HTTP/1.1

> Host: localhost:3000

> User-Agent: curl/8.6.0

> Accept: */*

>

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

< x-xss-protection: 0

x-xss-protection: 0

< x-content-type-options: nosniff

x-content-type-options: nosniff

#...(snip snip snip)...

< Content-Length: 0

Content-Length: 0

<

* Connection #0 to host localhost left intact

Focus on the lines * Connection #0 to host localhost left intact and

* Re-using existing connection with host localhost. Those are the evidence that the keep-alive is working.

For a comparison, let’s add Connection: close to the request header to test the keep-alive disabled.

$ curl -Iv http://localhost:3000 -o /dev/null http://localhost:3000 -H "Connection: close"

* Host localhost:3000 was resolved.

* IPv6: ::1

* IPv4: 127.0.0.1

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 0* Trying [::1]:3000...

* Connected to localhost (::1) port 3000

> HEAD / HTTP/1.1

> Host: localhost:3000

> User-Agent: curl/8.6.0

> Accept: */*

> Connection: close

>

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

< x-xss-protection: 0

< x-content-type-options: nosniff

#...(snip snip snip)...

< Connection: close

< Content-Length: 0

<

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 0

* Closing connection

* Hostname localhost was found in DNS cache

* Trying [::1]:3000...

* Connected to localhost (::1) port 3000

> HEAD / HTTP/1.1

> Host: localhost:3000

> User-Agent: curl/8.6.0

> Accept: */*

> Connection: close

>

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

< x-xss-protection: 0

x-xss-protection: 0

< x-content-type-options: nosniff

x-content-type-options: nosniff

#...(snip snip snip)...

< Connection: close

Connection: close

< Content-Length: 0

Content-Length: 0

<

* Closing connection

We see the line * Closing connection, so we know the keep-alive becomes off.

Additionally, the second connection says * Hostname localhost was found in DNS cache, which means

the second DNS look up hits the cache.

“When you type a URL in your browser, what will happen?” is the interesting question. We can learn how the Internet works as well as the network resource conservation and web performance.

References

- Optimizing HTTP: Keep-alive and Pipelining: https://www.igvita.com/2011/10/04/optimizing-http-keep-alive-and-pipelining/

- Mastering DNS: A Comprehensive Overview of Internet Address Translation

- Analysis of 7.5 Trillion DNS Queries Reveals Public Resolvers Dominate the Internet

- “1.1.1.1 is now handling more than 1.3T requests per day”: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=36984419

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol – HTTP/1.1: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc2616

- The Transport Layer Security (TLS) Protocol Version 1.2 https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc5246.txt

- Keep Alive: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Headers/Keep-Alive